A major advance in our knowledge of gromiids came in 1994 during a RRS Discovery cruise on the Oman margin of the Arabian Sea, when we discovered some large spherical organisms up to 3 cm or more in diameter and filled with sediment, living at depths below 1000 m. To cut a long story short, these ‘jellyballs’ turned out to be the first deep-water gromiids to be discovered. The crucial piece of evidence was the highly distinctive structure of the organic test wall, revealed in high voltage electron micrographs taken by our colleague Dr. Sam Bowser in Albany, New York. They were subsequently described as Gromia sphaerica (Gooday et al. 2000). An unusual feature of this species is the presence of multiple apertures scattered across the test surface.

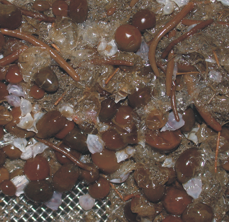

Further opportunities to sample in the Arabian Sea came during cruises aborad the R.R.S. Charles Darwin on the Oman margin (2002) and on the Pakistan margin (2003). In both areas, we collected many gromiid-like organisms at depths between 1000 m and 2200 m. Gromia sphaerica was again present, but this time the assemblages were dominated by grape- and sausage-shaped morphotypes ranging in size from 0.5 to 2 cm and with a single aperture. They occurred in abundances of up to 45 individuals per m2. In most cases, the ‘grapes’ and ‘sausages’ lived with their apertures buried in the organic-rich surface sediment (Figures 1 and 2). We were still not absolutely sure that they were gromiids but confirmation came from analysis of SSU rDNA gene sequences in the laboratory of Dr. Jan Pawlowski (Geneva). The analysis was done using previously developed Gromia oviformis specific primers, and results showed that deep-sea gromiids and Gromia oviformis branch together, with 100 confidence, next to other protistan groups such as Haplosporidians, Plasmodiophorans, Cercozoans and Foraminiferans (Aranda da Silva et al. 2006). Within deep-sea gromiids, there are at least seven species, confirmed with SSU rDNA analysis. Four of these seven species have distinct morphological characteristics. However, the other three which have grape-like shapes could not be distinguished purely on the basis of morphology, showing the existence of cryptic speciation. An eighth species has been described on the basis of its morphology (Gooday and Bowser 2005).